After a Friday afternoon of bouldering in Squamish, Ted Angus and I drove north of Pemberton to search for a mythical alpine climb called “The Mouse’s tooth”. Purportedly, “The best alpine climb on the coast.”

Specific route information for this climb is sparse. The route was put up within the last 5 years, so it is too new to be in Kevin McLane’s “Alpine Select.”

During my summer foray into being a climbing bum (living in Squamish out of my mum’s mini-van), this climb was recommended to me twice. I knew that it must be good.

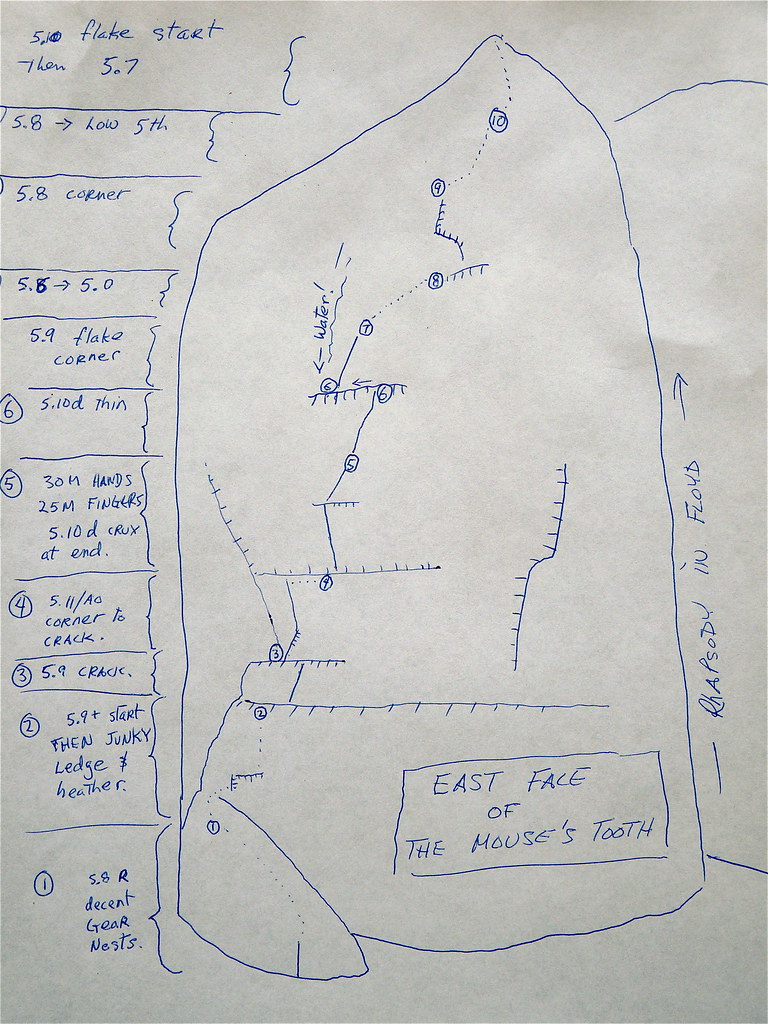

As per usual, my last minute planning meant that I did not know exactly how to find the climb. All that I had to work with was a brief description from Cascade Climbers, complete with a sketched topo. (plus the blog post previously linked). I wanted more information. I decided to phone my friend, Grant, to ask for more beta.

The drawn topo that we found on the route description from Cascade Climbers.

Grant proved to be moderately helpful, although he prefaced his driving directions with: “I’m not really sure, man. I was really high at the time.”

He did remember 3 useful pieces of information:

1) The Forest service road which leads to the approach trail is a left hand turn off of the Duffey Lake road

2) The approach trail is easy to lose, but it follows a drainage. If Ted and I were to lose the trail, he instructed us to bushwhack towards the river.

3) Offset nuts are highly recommended for the final (technical) pitch.

Armed with this additional beta, we still needed a better description of how to find the trailhead.

I phoned Nick Matwyuk, to inquire about the location of the “NJC FSR” described in the Cascade Climbers post. He kindly informed me that the North Joffre Creek FSR is the first (and only) left hand turn off of the Duffey lake road before the Joffre Lakes parking lot. This seemed to affirm point #1 of Grant’s advice.

With a full moon to illuminate our drive, Ted and I turned off of the highway onto what we figured must be the NJC FSR. The road immediately divided into the “West Joffre Mainline” (left) and “North Joffre Mainline” (right). We turned right onto the North Joffre Mainline.

According to the Cascade Climbers route description, we were supposed to take a “right hand spur road at 150m”. This confused me, because the fork dividing the West and North Mainlines was @ about 150m, but the North Mainline did not strike me as a “spur road”. I kept a vigilant eye out for potential “spur roads.”

Near the 1km sign, I saw a potential “spur road.” I consulted Ted, and we decided that it would be a good idea to drive up it, just in case it was the road we wanted.

It was not a good idea. My low clearance, 2wd Mazda protege, made a valiant effort to climb up the steep and bumpy road. This earned it only scrapes to its undercarriage.

At the top of the hill, we encountered a cutblock, which was clearly not part of the road description, so we turned back down. Fortunately, it is much easier to navigate rough roads when going downhill, so the journey back to the mainline left my mazda relatively unscathed.

After our trial (and error) run up the “spur road” Ted and I decided that the North Joffre Mainline must be the spur road that we were looking for. We followed it until the road became 4wd, then parked our car. We parked beside a “Squamish Adventures” truck that was perched on a log bridge.

Our parking location for the climb. About 4km up the North Joffre Mainline. The hiking starts straight ahead of where the two vehicles are parked. The Mouse’s Tooth is the hump of granite on the left.

On Saturday morning, I lazily awoke at around 06:00 to the sound of a white truck driving up the 4wd portion of the main road. I assumed this vehicle was being driven by a group of climbers who were also headed to the Mouse’s tooth. I later learned that it was probably full of loggers/workers. It surprised me that they would be working so early on a Saturday.

20 minutes later, another truck pulled up, and parked just down the hill from us. 2 people with hiking gear, obviously climbers, hopped out.

I crawled out of my sleeping bag to ask them if they were headed to climb the mouse’s tooth. It turned out that they were. To my surprise, they hiked right past our car onto a disused spur road that Ted and I didn’t even realize that we were parked on. I asked them if the trail was obvious. They informed me that it was. We would see flagging tape at the end of the road.

Little did they know, these climbers probably saved us from an epic. Based on the route description we had, Ted and I were planning to hike up the Joffre Mainline for what we expected to be “1/2 km of 4wd HC” until reaching the end of the road and the start of the trail. Who knows how far we would have ended up hiking on the main road before realizing that we were headed the wrong way.

Since we knew there were other people climbing the same route as us, Ted and I were in no rush to leave. We helped ourselves to a leisurely breakfast of cold oats and departed from the car at 07:45.

After crossing a river/ washout, we reached the end of the road and the start of the flagged/ cairned trail (just as expected).

We determined that my “odd cairn” spotting/ trail following spidey senses were better than Ted’s. I led the way. I managed to keep the trail most of the way, but was eventually flummoxed during the talus/ alder traverse towards the riverbed. I followed small trails through the brush, but they weren’t flagged. After about 500m of this, we regained the trail next to the river. Grant’s point of advice #2 proved helpful.

We slogged up the riverbed for about half an hour. After the cairns petered out, we reached a relatively flat section of the river. We crossed the river here, filled up on water, then hiked up the scree to the base of the climb.

We arrived at the base of the climb at around 09:30. The party ahead of us was about halfway up the first pitch. We learned that they were on the new 10d variation start, and we elected to climb the same way.

Ted were going to swing climbing leads. In order to give me the “scary” sounding pitches, Ted would lead pitch 1. This left me with the 5.11/A0 pitch 4 and the 5.10d THIN pitch 6.

We started climbing at around 10:15. Ted efficiently dispatched the blocky first pitch. It was a bit of a tricky pitch, because the shattered rock didn’t present an obvious “line” in the same way as the splitter cracks above.

I led the second pitch, which consisted of a V0 bouldering move past 2 bolts, and then 50m of heathery ledge scrambling.

The 3rd pitch, which Ted lead, was a cool 5.9 stemmy flake thing. While belaying Ted, I watched the party ahead of us cruise up the 4th pitch. The 5.11 finger crux looked tough, but they had no problems with it, so I was optimistic.

The 4th pitch was the start of the business. I started stemming up a thin corner crack, but quickly switched to laybacking. The gear was a little sparse in the shallow, flaring crack. Once I was up this portion, I reached a small ledge. Above the small ledge was a perfect splitter crack, starting with a cruxy fingers/thin hands section, and progressing into a hand crack.

I got distracted by chalked foot holds, and fell about 4 times while attempting the cruxy sequence off of the ledge. We were using half ropes, which are quite stretchy, so I fell a couple meters, even though I wasn’t far above my gear. Being the humble climber that I am, I had an excuse for my failure. I attributed one of my falls to the purple halfrope being snagged and tugging me down.

I finally pulled the crux sequence by ignoring the right footholds and jamming my right foot into the crack instead. The rest of the pitch was straightforward. The pitch finished with a 5m horizontal dyke traverse on two awesome ledges. A reasonable one for your hands and a thin one for your feet. I belayed Ted on a fixed anchor positioned under a 1m roof.

After cruising through the crux on his second attempt, it was Ted’s turn to lead the 5th pitch. The 5th pitch starts with a hand jam to pull the roof, then 30m of awesome hand crack, varying mostly between BD #2 and #3. Ted waltzed up this section, but then his upwards progress slowed to a halt. I sat for about 10 minutes or so before feeling any activity on the rope. I knew that Ted was resting on a ledge and trying to assess the 25m of thin, tapering finger crack above.

Eventually, I started feeding out rope again. Ted was moving. His progress was steady for a while. Then he paused again. After this second significant pause, he started moving again. He was moving quickly too. I continued feeding out rope to Ted until I heard a piercing cry. Then I braced for impact.

For me, the catch was anticlimactic. The stretchy green half rope absorbed all of the impact force. Two things made me fearful for Ted, though. The first was the massive loop of purple rope that was hanging below me. The length of loop in this rope was a good estimate of the distance that Ted had fallen.

More alarming, however, was the fact that I could actually hear Ted’s wail. Prior to his fall, I had not heard Ted at any of the previous belays. His deep voice didn’t project well, especially when he was competing with the noise of the turbulent river below.

Later, when Ted recounted the details of his fall, I attributed the amazing projection of his wail to three things: Increased sound wave amplitude, increased sound wave frequency, and directionality. The first point is obvious. The fear of falling made Ted yell louder.

The second point is also pretty intuitive. Usually when we yell louder, we yell in a higher pitch. Additionally, however, I believe there are two factors that are also important to mention with regards to the increased wave frequency of Ted’s yell. Even if slightly negligible, the effects of testicular strain (described by Ted later) and the doppler effect should not be ignored.

Finally, Ted caught his leg on the rope and inverted during his fall. His head was likely facing directly towards me whilst yelling. This would definitely help sound projection.

After catching Ted, I yelled up to inquire if he was alright. I didn’t get any response. Fortunately, tension was relieved from the green rope as he started to make upward progress. Soon, the loop of slack was gone from the purple rope. I continued to feed him out rope. He made it to the top without incident, and three sharp tugs on the ropes informed me that I should take him off belay.

I proceeded to crawl from the belay awkwardly under the roof to the start of the hand crack. The 30m of hand crack was superb, although I jammed my feet a little bit too well and my TC pro climbing shoes sometimes needed a little encouragement to get out of the crack.

I quickly made it to the ledge, where was treated to the sight of an impeccable, right arching finger crack. I also saw Ted. He appeared undamaged, and was talking to the members of the other party. They were setting up a rappel from the same anchor that I was climbing to.

I made my way up to a pretty good stance, before resting briefly while the first member of the other party started her rappel. I negotiated the very thin crux while she was still on rappel. There was a lot of gear and slings for me to take out of the crack. It appeared as though Ted had aided up this final section.

As I reached Ted at the belay, the second member of the other party began his rappel. Once he left, Ted divulged the details of his fall (some of which I have previously stated).

Right before the crux section, there is one pretty good stance. Ted placed his final piece of protection from this position. He realized that the crux section was going to be too thin and tenuous for him to easily place any more. After some positive self talk, Ted resolved to just “gun it” through the crux, to the next good stance… And he almost made it.

When he fell, he was well above his last piece. He managed to catch his leg on the rope and flip upside down as he plummeted for about 12 meters (he later paced this distance out on rappel). He scuffed up his helmet on the rock along the way. Fortunately, the fall was clean. He was mostly unharmed except for impact to his testicles from his harness.

Not wanting to take another big fall, Ted elected to aid through the crux on his second attempt. He promptly set up a belay, and proceeded to talk to the members of the other party.

It turns out that the two people ahead of us were both guides. The man was a mountain guide, while the woman was an alpine guide. They had both done the route before, and didn’t want to go to the top on this occasion. Apparently, pitch number 6 is really scary. The woman had recently recovered from an ankle surgery and elected not to lead it. Instead, she did a bushy 5’9 variation to the right. From the top of this pitch, The two guides decided to rappell. The climbing afterwards is relatively trivial, and they had climbed to the top before.

Ted passed on the information that the mountain guide had given him regarding the final technical pitch. He said that the required gear for the pitch was offset RPs. Ted owns regular RP’s, but we left them at the base of the climb. Ted also owns offset nuts (albeit not in small sizes), but he left these at home. This recommendation seemed to affirm the piece of advice #3 that Grant gave me.

Ted gave me the choice of what to do next. It was only 15:00, so we still had plenty of time. However, I didn’t feel up to the task of climbing a pitch that scared away an alpine guide. Especially since she cruised up the other two cruxy pitches on lead. She also had substantially larger biceps than me. It didn’t help that without the proper rock protection, I would be risking a much larger fall than Ted’s.

Ted was still frazzled from his fall. We did not feel inspired to bypass the scary pitch to gain the remaining 5.8/9 pitches that lead to the summit. With plenty of daylight left, Ted and I began our rappels. On the trail out, we followed the proper route through the talus. We returned to the car at 19:00.

Safely back at the car, we concluded that this was one of the very few instances where route traffic can be beneficial on a rock climb. The guides led us to the trail. They also saved us having to search for the base of the climb. Additionally, they gave us route advice on a potentially dangerous pitch. Finally, they didn’t slow us down. They were competent climbers and had been on the route before.

Although we didn’t reach the summit, Ted and I had an awesome time. I would highly recommend the Mouse’s tooth to anyone who is up to the grade! Pitches 3-5 were superb. I’m sure that pitch 6 is also awesome, but I’ll have to return with either a rope gun or more adequate nuts.

It’s all about nuts.

and testicular placement.